History

The 'Worcester Royal Porcelain Company Limited' was the result of the early work of Dr. John Wall and a group of 13 local businessmen who established a porcelain factory in 1751. Many experts believe Royal Worcester to be the oldest English porcelain brand still in existence today.

John Wall, a physician, and William Davis, an apothecary, were trying to develop a method of porcelain production that could then be used to boost prosperity and employment in Worcester, came into contact with the Bristol porcelain manufactory of Lund and Miller. They were using soapstone (a type of metamorphic rock) as a prime raw material in their porcelain production, this was a then-unique method for producing porcelain.

By 1756 Robert Hancock had arrived at Worcester, the first man to apply transferring of prints onto porcelain. The earliest Worcester porcelain being painted in blue under the glaze.

Source: VA Web Team under Creative Commons Licence 3.0

Around 1770 one of the first Royal dinner services was made for the Duke of Gloucester, four years later in 1774, Dr John Wall retired, his partners continuing to manufacture porcelain until their London agent, Thomas Flight purchased the factory and took over in 1783. He let his two sons run the concern, with John Flight taking the lead role till his death in 1791.

In 1788 George III, following a visit to the company, granted it a prestigious royal warrant, the word 'Royal' was added to the name.

During this period, the factory was in poor repair and production was limited to mostly Blue and White porcelain patterns after Chinese porcelain designs of the period. It was also pressured by competition from inexpensive Chinese export porcelain.

Thomas Flight died in 1800, leaving the factory in the hands of his son Joseph Flight and Martin Barr, who joined the firm as a partner in 1792;.

In addition to the warrant granted by George III, royal warrants were also issued by the Prince of Wales in 1807, and the Princess of Wales in 1808.

"Worcester porcelain" also includes the hard-paste porcelain made in Chamberlain's Factory and Grainger's Factory. Both of these began as decorating shops in Worcester, painting "blanks" made by other factories, however after a few years the factories began to make their own porcelain. Chamberlain's Factory, which was very high quality, (and in 1811 received its own royal warrant from the Prince Regent), had begun to manufacture by 1791. Grainger's Factory was making porcelain from 1807, though not of quite the highest quality.

In 1840, at a time when both businesses were having difficulties keeping up with a changing market, it merged with the main Flight and Barr concern as "Chamberlain & Company”.

In 1840 manufacture was consolidated on the current factory site and major modernisation followed in 1862.

Exhibition pieces were created, such as the Norman Conquest Vases, the Potters' Vases and the giant Chicago Vase, now on show at the Museum of Worcester Porcelain.

During the early 20th century Royal Worcester took a traditional approach to shapes and decoration, Royal Worcester's most popular pattern has been "Evesham Gold", first offered in 1961, depicting the autumnal fruits of the Vale of Evesham with fine gold banding on an "oven to table" body.

In 1976 Royal Doulton merged with Spode now becoming a producer of Porcelain and Fine China.

Backstamps and trademarks

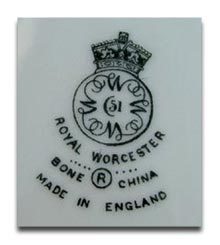

Worcester stamps have the number 51 in the center of a crescent to commemorate the company’s inaugural year. Marks without the 51 are very rare and date a piece pre 1783.

Much of the early Worcester pottery had irregular marks that weren’t always that neat, however post 1783, the clarity of these marks improved which makes dating more a little easier.

The Royal Mark

The Royal Worcester marks were first introduced in 1862, when the business restructured and became common place in 1867. These marks also incorporated the number 51 inside a crescent within a larger circle, with the crown just above. From 1876, the crown attached to the circle itself.

Royal Worcester printed mark, c.1876-91 – Photo by Antique Porcelain, antique Pottery

Royal Worcester date stamp 1912 – Photo by Worcester Fruit

Initially, Royal Worcester conveyed the year of production through the use of letters of the alphabet. In 1891, once those letters ran out, they implemented a code using dots. However this method became a little tedious, and by 1915 the marking system was changed again, as by that stage there were 24 dots around the Royal Worcester stamp. As a solution, in 1916, a small star was introduced around which dots would sit to represent each following year.

When the number of dots was changed each year, the company found it was cheaper and easier to add the extra dot to existing copper plates – making cost and time savings in the process by avoiding having to create new designs each year.

Royal Worcester introduced different shapes to the codes from 1928 until by 1941 they had three interlocking circles with nine dots arranged around them. The shapes included an open square, an open diamond, a division sign as well as circles and, of course, dots.

Worcester Marks – R and dots for 1959 – Photo by Antique Marks

By the 1980s some pieces had more elaborate marks, which often included issue numbers, the names of series and the designer’s name. In 1990, the factory stamps reverted to a letter R beneath the mark. They also had a number representing the lithographer and a date.

The Colours of the Marks

In the early years, Worcester marks were various colours, but from 1942 most were black or gold. In 1989, new factory stamps were introduced with an N replacing the previous M in a diamond under the rest of the mark, and then black numbers to identify the artist. In 1990, the colour changed to grey with a new lithographer identification. Then in 1996, the marks were printed in white to be even less intrusive.

Marks for Earthenware and Royal Worcester Vitreous

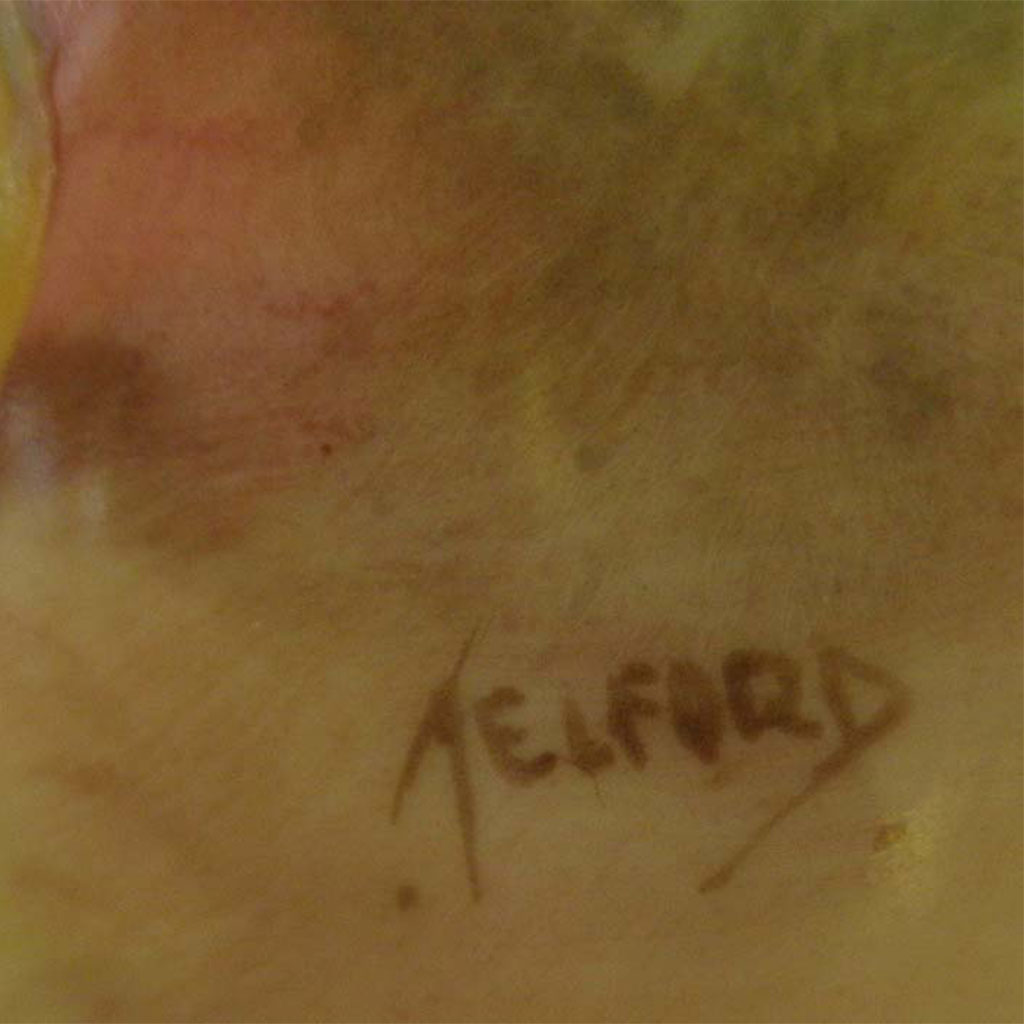

Although these sometimes followed the dot system, they often didn’t have a code at all, making identification of these wares a little tougher at times. Many did include an artist’s signature, as shown below, but not until the turn of the 20th Century.

Royal Worcester Hand Painted Vase with artist signature – Photo by Collectorium on Newcastle

Due to the fact that the Royal Worcester Company encouraged their artists to specialise in a particular style, identification of the artists is a little easier. Subjects range from highland cattle to soft roses, from birds and butterflies to fish and castles, and each had their specialists.

Indeed, Worcester was renowned for the beautiful decorations, often with a rich background colour of blue, green, turquoise or claret. Usually, they were formed by white framed panels, which the artists decorated with their paintings.

How to spot fake Royal Worcester

The faking of Worcester pottery has gone on for years. The inked backstamps themselves are relatively easy to fake, which is why you need to rely on other telltale signs to spot discern a real piece of Worcester versus an imposter. It’s always wise if you can to ask for the advice of an expert too, but the information below will help prevent you from being tricked by a counterfeit.

Hold it up to the light

There are plenty of clues to be had as to the authenticity of Worcester pottery, simply by holding a piece up to the light. There is a greenish tone to Worcester soapstone, while daylight will highlight any restoration, repairs or cover ups that have taken place.

Check for blemishes and cracks

If pieces claiming to be old Worcester have a crackle glaze, then they are fake, because the soapstone that authentic Worcester pottery is made from doesn’t craze (crazing being a glaze defect of glazed pottery, characterised as a spider web pattern of cracks penetrating the glaze and caused by tensile stresses greater than the glaze is able to withstand). Aside from the issue of spotting a fake, detecting surface cracks and imperfections will help you to judge the value of a piece too. Remember too that a plate with a crack will sound different to a plate that has had no damage at all, when tapped against your hand for example.

Be wary of more decorative pieces

Some pieces of Worcester are more highly sought after than others. For example, those with more intricate or higher levels of decoration. As a result, forgers often skin a piece - removing the original surface decoration and repainting in a more expensive design.

Another method used is clobbering - where new decoration is painted over the original, often just changing the ground colour. Look out for Worcester pieces that show any signs of damage or thicker paintwork than the usual.

Works / Pieces of note

Gorringe’s often sells pieces of Royal Worcester, with items from the pottery remaining popular to this day and fetching handsome sale prices, with a couple of examples below of lots that sold above estimate at auction.

A pair of Chamberlains Worcester armorial plates, 7.25in

Estimate £200-£250. Sold £400.

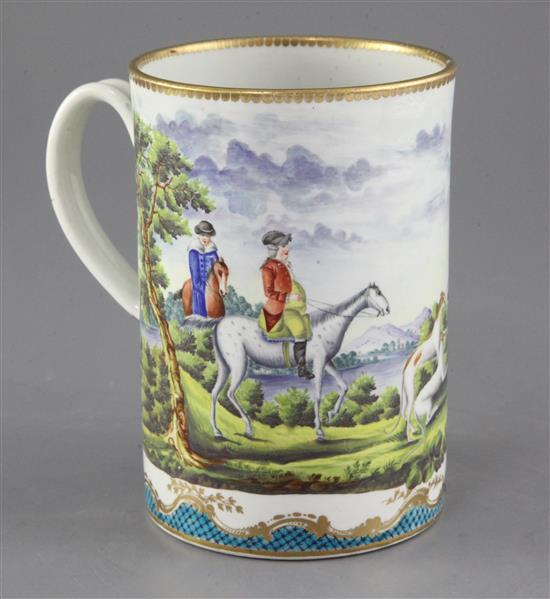

A rare Worcester tankard or mug, c.1780, 16cm high

Estimate £300-£500. Sold £650.

More recent history

When the factory celebrated its 250th anniversary in 2001, it would have just eight years more trading. The company went into administration on 6 November 2008 and on 23 April 2009, the brand name and intellectual property were acquired by Portmeirion Pottery Group – a pottery and homewares company based in Stoke-on-Trent. As Portmeirion Group had a factory in Stoke-on-Trent, the purchase did not include the Royal Worcester and Spode manufacturing facilities. The Worcester firm's Severn Street factory was closed with work moving to Stoke-on-Trent and abroad to cut costs.

The last trading date for Royal Worcester was 14th June 2009.

Further reading

https://www.museumofroyalworcester.org/learning/research/

https://learnantiques.com.au/

http://www.bbc.co.uk/herefordandworcester/content/articles/2008/01/10/wo...